A guide for preparing for illness, preventing spread to others, managing symptoms, and recovery

- PDF downloadable version of guide

- PDF downloadable version of sources

- PDF downloadable version of a one page summary

Table of Contents

- Summary

- Layers of Protection

- Planning Ahead

- When & How to Isolate

- Short Term Recovery

- Exiting Isolation

- Long Term Recovery

- Sources

1. Summary

View our abbreviated guide and full list of sources as well.

While you are healthy, it is important to plan ahead for illness. Despite the government consistently downplaying the disease and removing COVID protections,1 sustained high community transmission is all too common, increasing the risks of infection and reinfection for everyone. If you’re reading this guide before needing it, you are taking an important step towards being as prepared as possible!

| The People’s CDC has reviewed up-to-date research to create evidence-based guidelines and recommendations for what to do if you have COVID. Layers of Protection – You can help prevent the spread of COVID by using multiple layers of protection. – These layers include: ventilating and filtering air; masking with well-sealed and high filtration masks; staying up to date with vaccines and boosters; testing before seeing others; testing and isolating after possible exposures; and physical distancing and limiting time indoors. – If you’re at home with others while isolating due to infection or exposure, you can implement additional household-specific layers of protection. These include creating isolation zones, minimizing time spent in shared zones, and clearly communicating the use of layers of protection within your household. Planning Ahead – Improve the air quality of your home with humidifiers, purifiers, and open windows. – Have supplies, contact information (medical provider, testing, social supports), and a plan of action ready in case of illness. Familiarize yourself with your work or school’s COVID policy and devise ways to extend the 5-day isolation period, if possible. Exposure and Testing – If you’ve been exposed to someone who has COVID via shared air, you should isolate yourself for a minimum of 7 days. You should use multiple tests over the course of 5-7 days to determine if you are negative (1-2 tests over the course of the same 24 hours is not adequate). – If you test positive, you should isolate yourself for a minimum of 10 days after your first positive result. After 10 days, use rapid tests to find out if you are negative. – If you are experiencing symptoms, but do not have access to adequate testing, you should isolate yourself for a minimum of 10 days after the first day of symptoms. – If you test positive or experience symptoms, notify anyone you have seen in the past 7 days and share this guide, so that they can isolate and protect people around them as well. Short and Long Term Recovery – If you have COVID, we encourage you to speak with a medical provider about options for pharmaceutical treatments (such as Paxlovid or molnupiravir) as soon as possible. – The specific home remedies most helpful to you will depend on the symptoms you’re experiencing, but may include: over the counter pain relievers and fever reducers; cough suppressants and lozenges; and medicine to help you manage an upset stomach. – It is incredibly important to rest as much as possible both during and after your infection, as this appears to help with recovery and could potentially help prevent Long COVID. In general, we recommend that you avoid as much physical and mental exertion as possible both while you actively have COVID and in the weeks following your infection. – Continue to limit mental and physical exertion after recovering. We recommend following the pacing method as much as possible; you can find more information about specific recommendations for pacing in our full resource guide. Please note that this is for informational purposes only, and should not be considered medical advice. |

Throughout this guide, we provide detailed guidance and recommendations on planning ahead to protect yourself from infection, when to isolate in various situations, when and how to exit isolation, and how to prepare for short and long term recovery from COVID.

We at the People’s CDC recognize the challenges that people face in this country surrounding sick leave, health care coverage, and the end of the federal moratorium on evictions that can make isolating challenging. We hope our guidance can serve as an evidence-based approach to dealing with COVID exposures and infections.

2. Layers of Protection

COVID is an airborne virus that is spread through shared air. It has caused severe disease, chronic illness, and death in many people. All are vulnerable to the pandemic2, as Long COVID3 continues to impact previously healthy people—including children4—in unknown patterns5. Every COVID infection, and particularly reinfection6, has the chance to harm someone vulnerable and/or lead to Long COVID. Protecting ourselves is protecting our communities.

We use layers of protection7 principles throughout the guide. Layers of protection are tools and practices we use to prevent and dilute spread of virus particles. They include:

- Ventilating and filtering air

- Masking with well-sealed and high filtration masks

- Staying up to date with vaccines and boosters

- Testing before seeing others

- Testing and isolating after possible exposures

- Physical distancing and limiting time indoors

Not only are layers of protection particularly useful for isolating safely during a COVID infection, they’re also helpful for preventing respiratory infections in general. We recommend that you review our various resource guides8 for more information on COVID transmission and prevention.

3. Planning Ahead

Preparing Your Home

You can prepare your home by improving air quality and humidity. Since this is helpful for general respiratory health, the time you spend on preparation will be beneficial regardless of whether or not you become infected in the future. If you do become infected with COVID, and especially if you share your home with others, improving air quality and humidity will aid in your own recovery and help reduce the chance of infecting those with whom you live.

- Air quality: You can improve the air quality in your home by both ventilating it and purifying it.

- To improve ventilation: Keep windows open as much as possible. If you live alone or are not at risk of infecting others, open all of your home’s interior doors. If you have a fan, place it near your open windows or keep them on to improve air circulation in your home. Point fans away from people and towards areas of ventilation (such as exhaust vents, windows, etc). You may want to buy a carbon dioxide (CO2) sensor to assess ventilation; a CO2 level of 800 parts per million (ppm) or lower is a good level of aim for.

- To purify the air: Use HEPA filters9 with a clean air delivery rate (CADR) appropriate to room size. Choose a filter10 with a CADR at least two times the volume of your space11, aiming for at least six air changes per hour. Corsi-Rosenthal boxes12 are a cheaper, DIY13 alternative.

- Humidity: You should aim for a relative humidity (RH) between 40 to 60 percent in your home.

- A healthy humidity range is important for a few reasons: (1) RH in this range is not optimal for viruses15, which means they will die more quickly in such an environment. (2) RH in this range creates an environment in which viruses do not stay suspended in air for as long as they would in drier air. (3) RH in this range is more conducive to general lung health, whereas drier air is not. However, you should also be mindful not to go above this RH range—humidity above these levels may put your home at risk for mold growth. (For a longer explanation in easy-to-understand language, see Dr. Linsey Marr’s thread16 on this subject.)

- There are a few ways to measure relative humidity. CO2 sensors often come with that capability. If you don’t have a CO2 sensor, you can use one of the methods listed in this humidity measurement guide17.

Preparing for Illness

Preparing for the possibility of becoming ill may not have the “day to day” benefits that making general improvements to your home’s air quality or humidity will have, but it will help relieve some of the stress associated with scrambling for supplies, health care, or social support when or if you become sick. To help you prepare for the possibility of COVID infection, plan for the possibility of short- and long-term isolation periods, including potential rebound of illness, using the checklist below as a guide.

This checklist may only be a starting point for you, depending on your particular health or social needs. We also acknowledge this checklist will not be accessible to everyone, especially in the US where millions of people no longer have access to free testing, let alone paid time off from work, childcare, or easy access to medical providers and affordable, knowledgeable health care. Finally, please note that most of the items on this checklist are further explained in later sections of the guide or elsewhere on our website, which we have linked to within the checklist itself.

- Testing: Plan ahead for how to find PCR testing18. Have web resources or phone numbers handy in order to reliably find testing sites for when you contract COVID.

- Supplies: Stock up on over-the-counter medications and tools as discussed in Long COVID Justice’s webinar19: 19:

- Ibuprofen and/or acetaminophen

- Antihistamines or expectorants, cough syrup, cough drops. (You can also ask a pharmacist for suggestions tailored to your specific symptoms.)

- Thermometer

- Pulse oximeter

- Diary for tracking symptoms

- Rapid tests (4 or 5)20

- High filtration, well-sealed masks, such as N95, KN95, KF94 (minimum 2-3). See Masks below for more options.

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) monitors (1-2, optional)

- Health care: If you have access to a primary care provider, discuss with them ahead of time:

- A plan, should you get sick with COVID and require their assistance obtaining treatment or PCR testing.

- Confirm their accessibility during weekends or holidays, and identify alternative providers they can recommend if you become sick when they are not available.

- Locate your nearest urgent care facility, and assess whether it is an affordable and accessible option.

- Eligibility for antivirals (such as Paxlovid or molnupiravir) or IV medication (like remdesivir), especially if you have other health conditions, are 65 or older, or are taking other medications.

- A plan, should you get sick with COVID and require their assistance obtaining treatment or PCR testing.

- Employment and education: If your employer or school has a COVID policy, familiarize yourself with it. Do your best to advocate for as long an isolation period as possible until you are able to safely exit isolation (see Exiting Isolation). Consider discussing an isolation plan and a medical letter with your medical provider to provide to your place of employment or education.

- Social support: Identify people who can assist you while you are sick. Who might you be able to reach out to for moral support, groceries, meals, medications, or any other needs you have?

- Consider this pod mapping exercise21 for identifying people and communities to tap into for mutual aid and support.

- Run through this checklist again for any others in your household, particularly those under your care.

4. When & How to Isolate

There are two instances that prompt the need for isolation:

- Isolate after Exposure

- Isolate after Symptoms or Positivity

If you have to go out due to an emergency, or an employment, caregiving, or other responsibility, do your best to delegate to someone else who can address it, or to postpone, such as by using sick days if you have them. If you have no option but to go out, then use all layers of protection available to you to reduce the risk of spreading COVID to others.

Isolation after Exposure

If you were exposed due to proximity to someone with a confirmed case of COVID, you should isolate in case you were infected to prevent possible transmission to others.

We define exposure as having shared air with someone who had COVID at the time, for any amount of time and distance. Exposure happens on a continuum because it depends on the amount of viral particles shared by someone who has COVID. For example, if you encountered someone with COVID but you were both wearing high filtration masks, outdoors, and distanced, you are much less likely to contract COVID from them than if you were indoors together with no layers of protection. A situation in between, such as an indoor meeting with someone with COVID while you were both wearing surgical masks, still qualifies as an exposure (but is an improvement over no masking at all). Again, do your best to maximize the quality and quantity of your layers of protection in any situation, and isolate after you were around someone with confirmed COVID—the safest course of action for yourself and your community is to act under the assumption that you have an infection.

Isolation after Symptoms or Confirmed Positivity

If you start developing symptoms and/or confirm that you have COVID via testing or a medical provider’s diagnosis, you need to isolate to prevent transmission to others. If this happens, notify people you have seen in the past 7 days to let them know that they should isolate and test after exposure; share this guide with them as well. (See also Exiting Isolation.)

Common symptoms of COVID are sore throat, congestion, fever, cough, fatigue, and more23. If you develop symptoms or confirm positivity via testing or a diagnosis, you will need to isolate. Even mild symptoms are symptoms. Isolation is important regardless of how “bad” symptoms may feel.

Isolating Alone

In addition to calling on your resources (see Planning Ahead), be sure to rest and hydrate as much as you can. Try to limit going outdoors unless it is for essential needs, such as food or medical assistance. If you must go outdoors, wear a well-fitting, high-quality filtration mask at all times and limit your time outside your home to as short as possible.

Regularly check in with people from your pod for emotional and material support. An additional option is to reach out to emotional support warmlines, which are confidential phone lines staffed by peer volunteers who are in recovery, listed in the “Isolation and Support Groups” section of this document24 (p. 3).

Mark your calendar indicating when Day 0—the day your symptoms started, or if you had no symptoms, the day you tested—was. This way, you will have a sense of timing for when to end isolation.

Isolating with Household Members

Isolating after COVID exposure or during confirmed COVID diagnosis is best done alone. However, some situations arise where circumstances do not permit solo isolation. The purpose of isolation is to limit the spread of COVID, as well as promote a healthy recovery. When isolating with household members who have not been exposed or diagnosed, it is important to monitor all household members’ symptoms to ensure infection has not spread. If you are isolating because of a positive test or symptoms, your household members should follow isolation guidelines for exposure, as noted above, while taking measures to reduce the risk of infection transmission.

Outlined are five areas to focus on when isolating with household members who may have not yet been exposed or infected.

1. Masks

A well-sealed mask has a significant protective effect25 against COVID. All members of the household should have plenty of high filtration, well-sealed masks (e.g., N95, KN95, KF94). To ensure that you are buying masks certified by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, you can check their approval labels here26—the website also provides detailed instructions on how to check for certification.

If these are not accessible to you financially, you can request free masks from Bona Fide Masks, find discounts in the Masks for Everyone Reddit community, or inquire with your local health department. If you only have surgical masks, other options, which are less effective for reducing transmission27, are to double layer28 with a cloth mask on top of the surgical mask, use a mask frame29 to improve seal on your mask, or to use the mask alone, but knot and tuck to improve fit30.

2. Isolation Zones

Isolation zones are areas within the household where only one member will be during the isolation period. Depending on living arrangements, this could be a separate sleeping area for the individual who is isolating, such as a bedroom.

3. Shared Zones

Shared zones are areas within the household where more than one member of the household will be during the isolation period. These areas should not be occupied by the isolating individual and the non-isolating individual(s) at the same time but may need to be accessed by both throughout the day. Typical shared zones are kitchens, bathrooms, and other common spaces that all parties will need to access at some point during the isolation period. Individuals spending time in shared indoor spaces for more than a few minutes may be at risk31 for infection if one individual is infected with COVID. It is important to limit exposure in these areas and give ample time entering these zones after it has been occupied by someone in isolation. If possible, at least 30 minutes should pass between a person who is isolating occupying a space and a person who is not isolating. One option is to have the non-isolating individual(s) use the space first, followed by the isolating individual, so that there is adequate time for the virus to be cleared after the isolating individual uses the space.

4. Air Quality

Since COVID is airborne, reducing the amount of virus present through air quality control will reduce transmission between isolating and non-isolating household members. Blocking paths from isolation zones to shared zones, such as by applying painter’s tape on central air vents during the duration of isolation, can reduce the amount of virus traveling within the home. Other ways to reduce the amount of virus in the air include further opening windows in both isolation and shared zones, turning on exhaust fans, and using air purifiers.

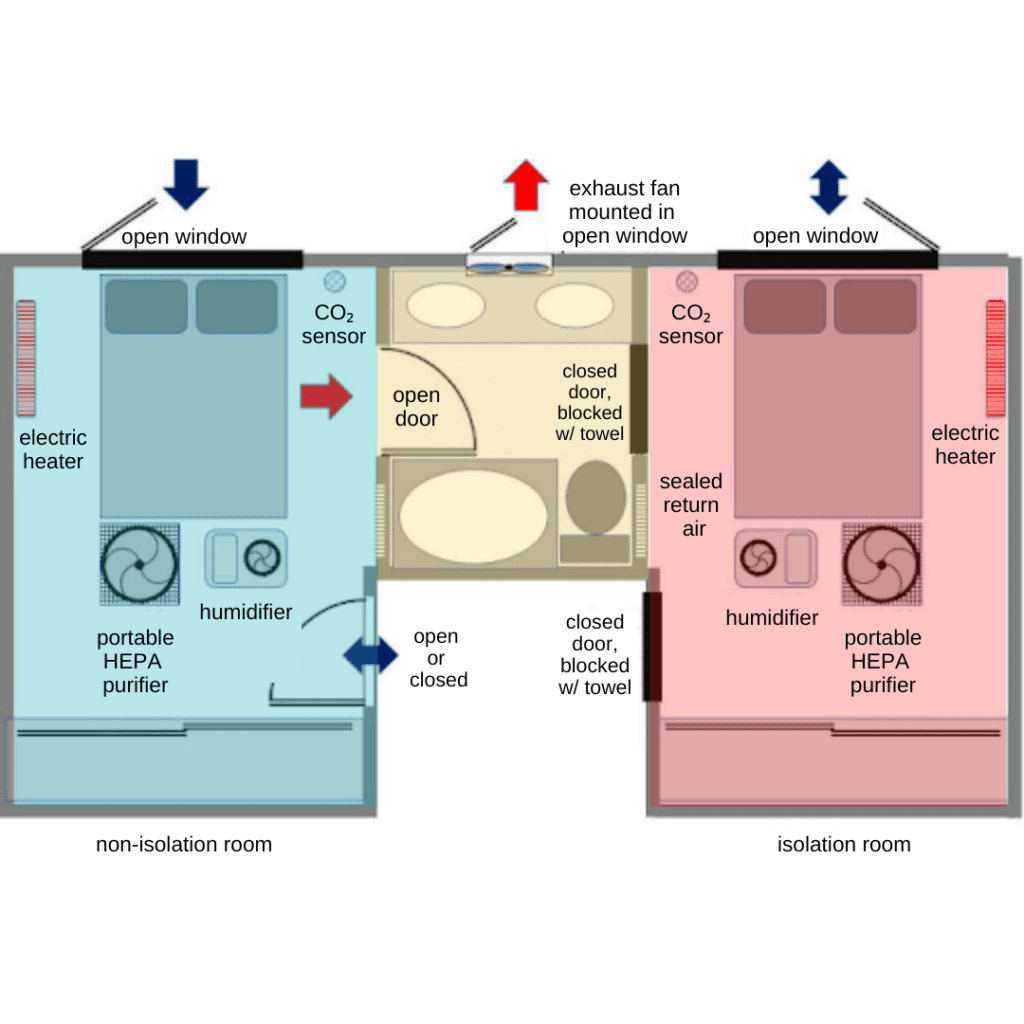

One example of how to configure your space to minimize indoor transmission is pictured here.

As adapted from Healthy Heating, which has diagrams of various home configurations for safely isolating with others, this setup allows for bathroom access by non-isolating individuals. The objective is to keep the air from the isolation bedroom from contaminating the rest of the home. Keep windows open as much as possible, except if the window or vent directs air to other parts of the home. Non-isolating individuals should coordinate with the isolating person so that the bathroom is used for as short a period of time as possible. To change over, the isolating person should vacate the bathroom, close the bathroom door, and remain in the bedroom. The bathroom exhaust fan and the HEPA purifiers that are in the bedrooms should be on at all times. After waiting about 30 minutes to let the bathroom air purge, a non-isolating person should enter with a mask on (N95 or similar if available), and seal the bottom of the isolation room door with a towel. As mentioned in Preparing Your Home, in addition to removing airborne particles with a HEPA purifier, keep the bedrooms at a healthy relative humidity with a humidifier. If your household has access to CO2 monitors, they can be placed in each bedroom. Aim for a CO2 level of 800 ppm or lower to ensure that you have fresh air and that COVID isn’t potentially building up indoors. You can use an electric space heater to maintain best acceptable thermal conditions during cold periods.

5. Communication

Discuss COVID layers of protection available to you and your household members before anyone falls ill: What do you have available? What do you need to stock up on? How will you implement the measures in this guide when someone is ill or isolating? It may help to list out the actions you will take, step by step. Then, if someone needs to isolate, remind everyone of the protocols you have agreed upon so that the process can be as straightforward as possible.

5. Short Term Recovery

Although recovery from COVID infection can look different from one person to another, it’s important to prepare for multiple types of recovery by planning ahead and before symptomatic infection, if possible. One way to plan ahead is by reviewing the information in this section, even if you are not currently experiencing a COVID infection.

In this section, we discuss considerations for short term recovery, including medication you can obtain from a medical provider or pharmacist, home remedies, tracking your symptoms, and the importance of rest. Later, we discuss long term recovery, where we provide a very brief overview of Long COVID and where to seek out resources should you have lingering symptoms following the acute infection.

Please note that this content is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please use this information as a starting point only, and be sure to consult with a medical professional who is familiar with your particular needs whenever possible.

COVID Medications

If you’ve tested positive for COVID, you should consult with a licensed medical provider or pharmacist to determine whether you qualify for any treatments that make sense for your particular needs. As we’ve reported in previous Weather Reports33, monoclonal antibody34 treatments are no longer available for COVID treatment, as they are not effective for newer variants35. Paxlovid36 has been shown to prevent hospitalization and death significantly in high risk groups (age 65 years and older, immunosuppressed people, people without vaccination, etc.). Although some people experience “rebound”37 after finishing a course of Paxlovid (or similar medications, such as molnupiravir)38, new research does suggest it could lower the risk of Long COVID39 by around 25%. For people who are at very high risk and may not be eligible for Paxlovid due to medical conditions or medication interactions, remdesivir40 is also an option. We encourage you to discuss with your medical provider what options for treatment are available to you in case of illness.

Generally, medications such as Paxlovid are described as being for those at “high risk of disease progression”41. In its COVID Treatment Guidelines42, the National Institutes of Health recommends that providers review the CDC’s “People With Certain Medical Conditions”43 to determine if a patient is “high risk” for severe outcomes of COVID. We encourage you to take a look at it, as it is quite extensive. You may qualify for “high risk” status due to various medical conditions (including COPD, diabetes, and many more), disabilities (including learning disabilities and ADHD), mental health conditions (such depression or other mood disorders), and even various behaviors (including physical inactivity or having been a former smoker). In these guidelines, the CDC also notes that “some people are at increased risk of getting very sick or dying from COVID because of where they live or work, or because they can’t get health care,” including “many people from racial and ethnic minority groups.” As a result, most people qualify for this definition because of government failure to eliminate inequities or provide safeguards in our communities.

You can use this tool44 from the Department of Health and Human Services to find medication, such as Paxlovid, for COVID. In the screenshot below, you can see an example of a search for a specific zip code, with results for both “test-to-treat” locations (where you can access testing and medication at the same location) as well as locations that are likely to be able to fill a prescription. In some cases45, pharmacists can prescribe Paxlovid; in others, you may need a licensed medical provider to write you a prescription. If eligible, you should do your best to obtain treatment as soon as possible—it must be taken within 5 days46 of the start of your symptoms.

It’s important to consult with a medical professional before taking these medications because they may interact with many other medications47 (including certain cholesterol medications, blood thinners, etc.). There are also certain medical conditions48 that may limit or determine what treatments are available. If you would like to check if any of your medications may interact with a COVID treatment, you can use this tool49,50 and ask your medical provider. You should also be aware of the possibility of rebound; this term is used to describe the reemergence of COVID symptoms and/or a positive COVID test51 following a full course of Paxlovid or molnupiravir. Rebound may mean you are contagious again, but it is not a reason to avoid treatment. As we have mentioned before, taking medication for COVID infection can reduce viral replication and limit the severity of symptoms, while also reducing risk of Long COVID.

Unfortunately, it may be difficult to obtain these medications depending on your geographic location and access to health care in general. What’s more, the process by which people access these and future drugs will soon be made even more difficult to obtain due to the current administration’s push for a full “commercialization” of COVID vaccines, testing,52 and treatments.53

Home Remedies

Whether or not you’re able to receive Paxlovid or other treatments from your medical provider, you’ll want to have a few other things on hand to help manage your symptoms.

Symptoms of COVID often differ from person to person and from variant to variant54; for example, although some variants have loss of smell and taste as their primary symptom, other variants may not cause that particular symptom at all. Depending on your particular symptoms, you may find relief from over the counter pain relievers and fever reducers; cough suppressants and lozenges; and medicine to help you manage an upset stomach. Please refer to the Supplies checklist for more details.

You may also want to consider remedies for decreasing symptom time or severity of COVID. The guide55 indicates supplements and behaviors that should reduce risk, as well as items that are likely safe and items to avoid, based on existing evidence.

Tracking Your Symptoms

Tracking the symptoms you experience while COVID positive will help you determine if you should seek out additional medical intervention. You can aim to track once daily, or as symptoms change.

To track your symptoms, you should consider investing in a pulse oximeter to help track symptoms related to your heart rate and blood oxygenation. Unfortunately, pulse oximeters do not always work adequately56, with readings often showing a falsely higher reading57 than is accurate in patients with darker skin. This is why, regardless of what the meter says, if you are having chest pain or difficulty breathing, you should go to the emergency room. You will also want to have a thermometer on hand to help track fevers, and rapid tests to help you determine whether or not you are still actively positive. Please refer to the Supplies checklist for more details.

You can track your symptoms in a diary like this:

The Importance of Rest

Along with treating COVID symptoms through medications obtained from a medical provider or pharmacist and/or through various home remedies as discussed throughout this guide, it’s also important to allow yourself to rest. Though there is a popular belief that physical exercise is beneficial and should be encouraged when recovering from COVID, there is a growing body of research showing that physical overexertion can actually have adverse effects58. And, although this research is ongoing, “many researchers, patients, and advocates say [rest] is one of the most powerful tools for managing, and potentially even preventing, Long COVID” 59 (see Long Term Recovery).

A great place to start while you’re in the acute phase of COVID is with #MEAction’s Pacing and Management Guide60, which provides simple instructions and examples for how to avoid post-exertional malaise for both adults and children. In general, we recommend that you avoid as much physical and mental exertion as possible both while you actively have COVID and in the weeks following your infection. After your infection, pace yourself.

6. Exiting Isolation

Determining when to exit isolation can be as important as determining when to begin isolation. Exiting isolation can depend on the purpose of isolation, either exposure or infection.

Exiting Isolation after Exposure

The average incubation period,61 or time it takes from initial exposure to becoming ill with COVID, is 6.57 days. As a result of this, we recommend testing 7 days after exposure61 to avoid false-negative test results. You can exit isolation 7 days after exposure following two negative tests with at least 24-hour interval between samplings.

Note that incubation periods have a wide range, typically from 1 to 14 days. If it is possible, the best practice is to remain isolated for 14 days after exposure to ensure that you remain symptom free62.

When exiting isolation, it is still important to monitor symptoms and continue to maintain social distancing and masking in case of false-negative testing. We also recognize that in the US with no guaranteed sick leave, no moratorium on evictions, and no universal health coverage, our guidelines and recommendations may not be available to you.

After exiting isolation, and especially if you are unable to remain isolated for a full 14 days, do your best to use all layers of protection that you have to minimize risk to others, including using a well-fitting, high-filtration mask in public spaces.

Exiting Isolation after Infection

If isolation is due to a confirmed COVID diagnosis, we recommend isolating for a minimum of 10 days63. After 10 days since confirmed positivity, a negative test can determine if it is safe to exit isolation. If symptoms are still present, it is recommended to remain in isolation until symptoms have resolved and two negative tests, with at least a 24-hour interval in between tests, have been produced. If you are experiencing symptoms, but do not have access to adequate testing, you should isolate yourself for a minimum of 10 days after the first day of symptoms.

As mentioned in Exiting Isolation after Exposure, it is still important to monitor symptoms and continue to maintain social distancing and masking in case of false-negative testing. After exiting isolation, do your best to use all layers of protection that you have to minimize risk to others, including using a well-fitting, high-filtration mask in public spaces.

7. Long Term Recovery

Once you’ve passed the acute phase of COVID, you may experience lingering effects and symptoms that you may or may not have experienced during your active infection. For example, some people who experience loss of taste or smell during the acute phase continue to experience loss of taste or smell64 for an extended period of time. Others report extended periods of breathlessness65, brain fog66, fatigue67, and other symptoms68. There is a link between COVID infections and medical issues months, or even years, after the initial infection, including increased risk for heart attack or stroke69, diabetes70, cancer71, and other serious medical conditions. Researchers have also begun to uncover a link between COVID infections and immune dysregulation72, meaning that if you have had COVID you may be at higher risk for more severe illness from COVID and other infections in the future. Collectively, we refer to these lingering symptoms as Long COVID.

The rates at which people experience Long COVID vary. The CDC estimates that at least one in five adults73 who’ve been infected with COVID will go on to experience Long COVID. However, this is only one of many different estimates74. Childrens’ experiences with Long COVID75 have also been well documented.

Although a thorough review of Long COVID (including potential mechanisms by which COVID leads to Long COVID in children and adults, specific short and long term symptoms, and possible treatments) is well beyond the scope of this particular guide, it’s important for you to understand it to be a possibility and to be prepared to seek out resources that can help you better understand your symptoms, obtain support, and explore possible treatments.

As the federal government and CDC continue to downplay Long COVID, patient-led groups and organizations have taken the lead in doing this essential work. To prepare, we recommend familiarizing yourself with groups such as Long Covid Families76 and #MEAction,77 and The Network for Long COVID Justice19,21 as a starting point should you need additional information or guidance.

Good luck, and please continue to do all that you can to protect yourself and your community from COVID. Remember: we keep each other safe!

Sources

View our abbreviated guide and full guide here.

1. People’s CDC. (2022, November). Safer Gatherings Toolkit: Community Care First! www.seeyousafer.org

2. Barber, C. (2022, October 6). Strokes, heart attacks, sudden deaths: Does America understand the long-term risks of catching COVID? Fortune. https://fortune.com/2022/10/06/strokes-heart-attacks-sudden-death-america-long-term-risks-catching-covid-carolyn-barber/

3. CDC. (2022, September 1). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/

4. Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Ayuzo del Valle, N. C., Perelman, C., Sepulveda, R., Rebolledo, P. A., Cuapio, A., & Villapol, S. (2022). Long-COVID in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 9950. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13495-5

5. Xu, E., Xie, Y., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02001-z

6. Bowe, B., Xie, Y., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02051-3

7. People’s CDC. (2022). Layers of protection: Strategies to reduce COVID-19 infection and spread. https://peoplescdc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Layers-of-protection.pdf

8. People’s CDC Resources. https://peoplescdc.org/category/resources/

9. Clean Air Crew. Air Cleaner Guide. https://cleanaircrew.org/air-cleaners/

10. Clean Air Stars. Air Filter Recommendation Tool. https://cleanairstars.com/filters/

11. Vanzo, T. (2021, October 18). How to Choose an Office Air Purifier. https://smartairfilters.com/en/blog/how-to-choose-an-office-air-purifier-guide/

12. Rosenthal, J. (2020, August 22). A Variation on the “Box Fan with MERV 13 Filter” Air Cleaner. https://www.texairfilters.com/a-variation-on-the-box-fan-with-merv-13-filter-air-cleaner/

13. Rogers, A. (2020, August 6). Could a Janky, Jury-Rigged Air Purifier Help Fight Covid-19? Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/could-a-janky-jury-rigged-air-purifier-help-fight-covid-19/

14. Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, December 23). Ventilation helps protect against the spread of COVID-19. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/ventilation-helps-protect-against-spread-covid-19.html

15. Lin, K., & Marr, L. C. (2020). Humidity-Dependent Decay of Viruses, but Not Bacteria, in Aerosols and Droplets Follows Disinfection Kinetics. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(2), 1024–1032. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b04959

16. Marr, L. C. (2020, December 27). Humidity and Airborne Viruses. https://mobile.twitter.com/linseymarr/status/1343318611218345987?s=20&t=Me1S4ssylGFW3hiLrTbD4g

17. Deljo Heating and Cooling. How to Find the Right Humidity Level in Your Home. https://deljoheating.com/blog/how-to-find-the-right-humidity-level-in-your-home/

18. People’s CDC. (2022, September 12). COVID Testing Guide. https://peoplescdc.org/2022/09/12/testing/

19. LongCOVID Justice (Director). (2022, October 6). Managing Illness at Home. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJeUw7h9SKw&t=288s

20. Having 4 or 5 per person is helpful for repeat testing. However, keep track of expiration dates. The FDA has listed the names of rapid test brands whose shelf life go beyond the labeled expiration date. See the list here.

21. LongCOVID Justice (Director). (2022, October 6). Managing Illness at Home. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJeUw7h9SKw&t=560s

22. Mingus, M. (2016, June). Pods and Pod Mapping Worksheet. Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective. https://batjc.wordpress.com/resources/pods-and-pod-mapping-worksheet/

23. Zoe Health Study Staff. (2022, December 8). What are the most common COVID symptoms? https://health-study.joinzoe.com/blog/covid-new-top-10-covid-symptoms

24. FEMA. (2020). COVID-19 Best Practice Information: Mental Health Support. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/fema_covid_bp_mental-health-support.pdf

25. Li, Y., Liang, M., Gao, L., Ayaz Ahmed, M., Uy, J. P., Cheng, C., Zhou, Q., & Sun, C. (2021). Face masks to prevent transmission of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of infection control, 49(7), 900–906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.12.007

26. The National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory. (2021, September 15). NIOSH-Approved Particulate Filtering Facepiece Respirators. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/disp_part/default.html

27. CDC. (2022, February 11). Effectiveness of Face Mask or Respirator Use in Indoor Public Settings for Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 Infection—California, February–December 2021 (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)). http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7106e1

28. Brooks, J. T., Beezhold, D. H., Noti, J. D., Coyle, J. P., Derk, R. C., Blachere, F. M., & Lindsley, W. G. (2021, February 19). Maximizing Fit for Cloth and Medical Procedure Masks to Improve Performance and Reduce SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Exposure, 2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(7), 254–257. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7007e1

29. CDC. (2022, September 8). Types of Masks or Respirators. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/types-of-masks.html

30. CDC. (2021, April 15). How to Knot and Tuck Your Mask to Improve Fit. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GzTAZDsNBe0&t

31. Riediker M, Tsai D. Estimation of Viral Aerosol Emissions From Simulated Individuals With Asymptomatic to Moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(7):e2013807. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13807. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2768712

32. Bean, R. (2021). How to set up an emergency isolation room inside a home or apartment for a suspected infected occupant. Healthy Heating. https://www.healthyheating.com/2021.COVID.Residential.Isolation.Rooms/2021.Residential.Isolation.Room.htm

33. People’s CDC. (2022, December 5). People’s CDC COVID-19 Weather Report. People’s CDC. https://peoplescdc.org/2022/12/05/peoples-cdc-covid-19-weather-report-25/

34. COVID Real-Time Learning Network. (2022, December 20). Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibodies. https://www.idsociety.org/covid-19-real-time-learning-network/therapeutics-and-interventions/monoclonal-antibodies/

35. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2022, December 1). Once A Covid ‘Miracle,’ Monoclonal Antibodies Are No Longer Available. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/morning-breakout/once-a-covid-miracle-monoclonal-antibodies-are-no-longer-available/

36. Arbel, R., Wolff Sagy, Y., Hoshen, M., Battat, E., Lavie, G., Sergienko, R., Friger, M., Waxman, J. G., Dagan, N., Balicer, R., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Peretz, A., Yaron, S., Serby, D., Hammerman, A., & Netzer, D. (2022). Nirmatrelvir Use and Severe Covid-19 Outcomes during the Omicron Surge. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(9), 790–798. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204919

37. Samuels, F. M. D. (August 8, 2022). What Is Paxlovid Rebound, and How Common Is It? Scientific American. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-paxlovid-rebound-and-how-common-is-it/

38. Wang, L., Berger, N. A., Davis, P. B., Kaelber, D. C., Volkow, N. D., & Xu, R. (2022). COVID-19 rebound after Paxlovid and Molnupiravir during January-June 2022. MedRxiv, 2022.06.21.22276724. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.21.22276724

39. Xie, Y., Choi, T., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Nirmatrelvir and the Risk of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (p. 2022.11.03.22281783). medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.03.22281783

40. National Institutes of Health. (2022, December 1). Remdesivir. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antivirals-including-antibody-products/remdesivir/

41. Najjar-Debbiny, R., Gronich, N., Weber, G., Khoury, J., Amar, M., Stein, N., Goldstein, L. H., & Saliba, W. (2022). Effectiveness of Paxlovid in Reducing Severe COVID-19 and Mortality in High Risk Patients. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, ciac443. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac443

42. NIH. (2022, December 1). Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid). COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antivirals-including-antibody-products/ritonavir-boosted-nirmatrelvir–paxlovid-/

43. CDC. (2022, December 6). People with Certain Medical Conditions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

44. HHS Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response. COVID Test to Treat Locator. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://covid-19-test-to-treat-locator-dhhs.hub.arcgis.com/

45. FDA. (2022, July 7). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Pharmacists to Prescribe Paxlovid with Certain Limitations. FDA; FDA. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-pharmacists-prescribe-paxlovid-certain-limitations

46. Pfizer. FAQs | PAXLOVIDTM (nirmatrelvir tablets; ritonavir tablets) For Patients. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://www.paxlovid.com/faq

47. Aungst, C. (2022, July 8). How to Get Paxlovid if You Have Covid (And More Tips). GoodRx. https://www.goodrx.com/paxlovid/how-to-get-paxlovid

48. FDA. (2022, August 26). PAXLOVID Patient Eligibility Screening Checklist Tool for Prescribers. https://www.fda.gov/media/158165/download

49. University of Liverpool. COVID-19 Drug Interactions. https://www.covid19-druginteractions.org/checker

50. The list of Paxlovid drug interactions from Michigan Medicine may also come in handy.

51. Skerrett, P. (2022, August 2). Paxlovid Rebound Happens, though Why and to Whom are Still a Mystery. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2022/08/02/paxlovid-rebound-mystery/

52. Brenda Goodman. (2022, August 16). Biden Administration will Stop Buying Covid-19 Vaccines, Treatments and Tests as Early as This Fall, Jha says. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/16/health/biden-administration-covid-19-vaccines-tests-treatments/index.html

53. Croft, J. (2022, December 7). When Feds Pull Subsidy, Cost of Paxlovid Will Hit Americans Hard. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/covid/news/20221207/when-feds-pull-subsidy-cost-of-paxlovid-will-hit-americans-hard

54. People’s CDC. (2022, September 12). Major US Variants. Major US Variants. https://peoplescdc.org/2022/09/12/major-us-variants/

55. Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine. Integrative Recommendations. https://drive.google.com/file/d/15n-90qAHDZ1nhWBJd0hbVjgLbNbkuMDm/view, as found on https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/resources.html#covid

56. Bickler, P. E., Feiner, J. R., & Severinghaus, J. W. (2005). Effects of Skin Pigmentation on Pulse Oximeter Accuracy at Low Saturation. Anesthesiology, 102, 715–719. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200504000-00004

57. Bridger, H. (2022, July 14) Skin Tone and Pulse Oximetry. Harvard Medical School. Retrieved December 9, 2022, from https://hms.harvard.edu/news/skin-tone-pulse-oximetry

58. Wright, J., Astill, S. L., & Sivan, M. (2022). The Relationship between Physical Activity and Long COVID: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095093

59. Why You Should Rest—A Lot—If You Have COVID-19. (2022, September 23). Time. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://time.com/6215346/covid-19-rest-helps/

60. #MEAction Network. Pacing and Management Guide. #MEAction Network. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.meaction.net/resource/pacing-and-management-guide/

61. Wu, Y., Kang, L., Guo, Z., Liu, J., Liu, M., & Liang, W. (2022). Incubation Period of COVID-19 Caused by Unique SARS-CoV-2 Strains: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 5(8), e2228008. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28008

62. Zaki, N., & Mohamed, E. A. (2021). The Estimations of the COVID-19 Incubation Period: A Scoping Reviews of the Literature. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 14(5), 638–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.01.019

63. Adam, D. (2022). How Long is COVID Infectious? What Scientists Know so far. Nature, 608(7921), 16–17. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-02026-x

64. Lechner, M., Liu, J., Counsell, N., Ta, N. H., Rocke, J., Anmolsingh, R., Eynon-Lewis, N., Paun, S., Hopkins, C., Khwaja, S., Kumar, B. N., Jayaraj, S., Lund, V. J., & Philpott, C. (2021). Course of symptoms for loss of sense of smell and taste over time in one thousand forty-one healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: Our experience. Clinical Otolaryngology, 46(2), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13683

65. Sigfrid, L., Drake, T. M., Pauley, E., Jesudason, E. C., Olliaro, P., Lim, W. S., Gillesen, A., Berry, C., Lowe, D. J., McPeake, J., Lone, N., Munblit, D., Cevik, M., Casey, A., Bannister, P., Russell, C. D., Goodwin, L., Ho, A., Turtle, L., … Scott, J. T. (2021). Long Covid in adults discharged from UK hospitals after Covid-19: A prospective, multicentre cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 8, 100186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100186

66. Asadi‐Pooya, A. A., Akbari, A., Emami, A., Lotfi, M., Rostamihosseinkhani, M., Nemati, H., Barzegar, Z., Kabiri, M., Zeraatpisheh, Z., Farjoud‐Kouhanjani, M., Jafari, A., Sasannia, S., Ashrafi, S., Nazeri, M., Nasiri, S., & Shahisavandi, M. (2022). Long COVID syndrome‐associated brain fog. Journal of Medical Virology, 94(3), 979–984. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27404

67. Stavem, K., Ghanima, W., Olsen, M. K., Gilboe, H. M., & Einvik, G. (2021). Prevalence and Determinants of Fatigue after COVID-19 in Non-Hospitalized Subjects: A Population-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042030

68. Lubell, J. (2022, April 29). Long COVID: Over 200 symptoms, and a search for guidance. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/long-covid-over-200-symptoms-and-search-guidance

69. Xie, Y., Xu, E., Bowe, B., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine, 28(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

70. Xie, Y., & Al-Aly, Z. (2022). Risks and burdens of incident diabetes in long COVID: A cohort study. The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology, 10(5), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00044-4

71. Saini, G., & Aneja, R. (2021). Cancer as a prospective sequela of long COVID‐19. Bioessays, 43(6), 2000331. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202000331

72. Phetsouphanh, C., Darley, D. R., Wilson, D. B., Howe, A., Munier, C. M. L., Patel, S. K., Juno, J. A., Burrell, L. M., Kent, S. J., Dore, G. J., Kelleher, A. D., & Matthews, G. V. (2022). Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature Immunology, 23(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-01113-x

73. CDC. (2022, September 1). Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/

74. Ledford, H. (2022). How common is long COVID? Why studies give different answers. Nature, 606(7916), 852–853. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01702-2

75. Buonsenso, D., Munblit, D., De Rose, C., Sinatti, D., Ricchiuto, A., Carfi, A., & Valentini, P. (2021). Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992), 110(7), 2208–2211. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15870

76. Long Covid Families. Long Covid: Get the basics on Long Covid – also known as Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (PASC). Long Covid Families. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://longcovidfamilies.org/learn-about-long-covid/77. #MEAction. Long COVID & ME: Understanding the Connection. #MEAction Network. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.meaction.net/long-covid-me-understanding-the-connection/